The Canadian government says a federal judge misinterpreted the Charter of Rights and Freedoms in directing officials to secure the release of four men from detention in northeastern Syria.

Government lawyers are set to stress that point in the Federal Court of Appeal today as they seek to overturn a January ruling by Federal Court Justice Henry Brown.

In his decision, Brown said Ottawa should request repatriation of the men in Syrian prisons run by Kurdish forces as soon as reasonably possible and provide them with passports or emergency travel documents.

Brown ruled the men are also entitled to have a representative of the federal government travel to Syria to help facilitate their release once their captors agree to hand them over.

The government says in written arguments filed in the Court of Appeal that Brown mistakenly conflated the recognized Charter right of citizens to enter Canada with a right to return — effectively creating a new right for citizens to be brought home by the Canadian government.

Federal lawyers argue Brown’s «novel and expansive» approach overshoots the text, purpose and protected interests of the Charter right to enter, and is inconsistent with established domestic and international law.

The government also contends the court usurped the role of the executive over matters of foreign policy and passports. «The mandatory actions fail to respect the proper role of the executive and prevent it from making necessary, timely and individualized assessments within its expertise about a range of complex considerations.»

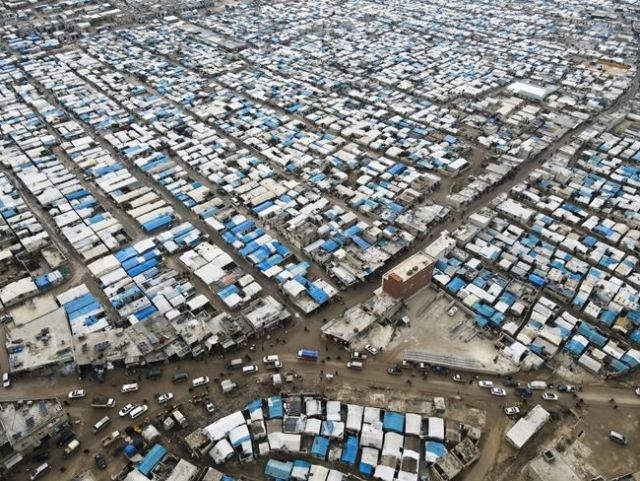

The judge’s ruling has largely been put on hold while the appeal plays out. However, Ottawa must still get the process started by initiating contact with the Kurdish forces who are detaining the men in a region reclaimed from the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant.

The four men include Jack Letts, whose parents John Letts and Sally Lane have waged a vigorous campaign to pressure Ottawa to come to his aid.

Lawyer Barbara Jackman, who represents Letts, points out in a submission to the Court of Appeal that the four Canadian men have not been charged with any crime.

«They have not had access to the necessities of life and have been subjected to degrading, cruel and unusual treatment during their nightmarish tenure in Syrian prisons,» the filing says. «Jack Letts told his family and the Canadian government that he was subjected to torture and contemplated ending his own life.»

The identities of the three other Canadian men are not publicly known.

Their lawyer, Lawrence Greenspon, says Brown’s ruling that Canada should take steps to facilitate repatriation of the men is a practical solution that recognizes the Charter-entrenched right of entry.

«Justice Brown’s decision is comprehensive and correct in law,» Greenspon’s written submission to the Court of Appeal says.

In these rare circumstances, where Canadians are being arbitrarily detained in a foreign country and the federal government has been invited to take steps to facilitate their entry into Canada, the court correctly declared that Ottawa should take those steps, the filing adds.

Family members of the men, as well as several women and children, argued in the Federal Court proceedings that Global Affairs Canada must arrange for their return, saying that refusing to do so violates the Charter.

The government insisted that the Charter does not obligate Ottawa to repatriate the Canadians held in Syria.

However, Greenspon reached an agreement with the federal government in January to bring home six Canadian women and 13 children who had been part of the court action.

In his ruling, Brown said the Canadian men are not able to return home «in part because their government seems never to have formally requested their repatriation.»

They are not able to enjoy «a truly meaningful exercise» of their Charter right to enter Canada unless and until the federal government makes a formal request to the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria on their behalf, he wrote.

«Canada must make a formal request for their repatriation because otherwise the Court is asked to construe the Charter in an ‘unreal world.»’